Bladder pain syndrome (BPS) is sometimes called painful bladder syndrome (PBS) or interstitial cystitis (IN-ter-STISH-ul sis-TY-tis) (IC). It is a long-term, painful condition of the bladder.

A “syndrome” is a collection of symptoms associated with a condition.

The official definition doctors use for BPS is long-term (more than a few months) pain or pressure which feels like it originates in the bladder and is accompanied by other urinary symptoms, such as a constant urge to empty the bladder and the need to go to the toilet more often. These symptoms usually increase when the bladder fills up. It usually gets better after emptying the bladder but soon returns. The pain can feel like it is spreading into the groin, the genital area or towards the lower back. In a subgroup of patients with BPS, lesions can be seen in the inner lining of the bladder but not all people with bladder pain have them.

Experts don’t know exactly what causes BPS but we do know that people with BPS seem to have the following in common:

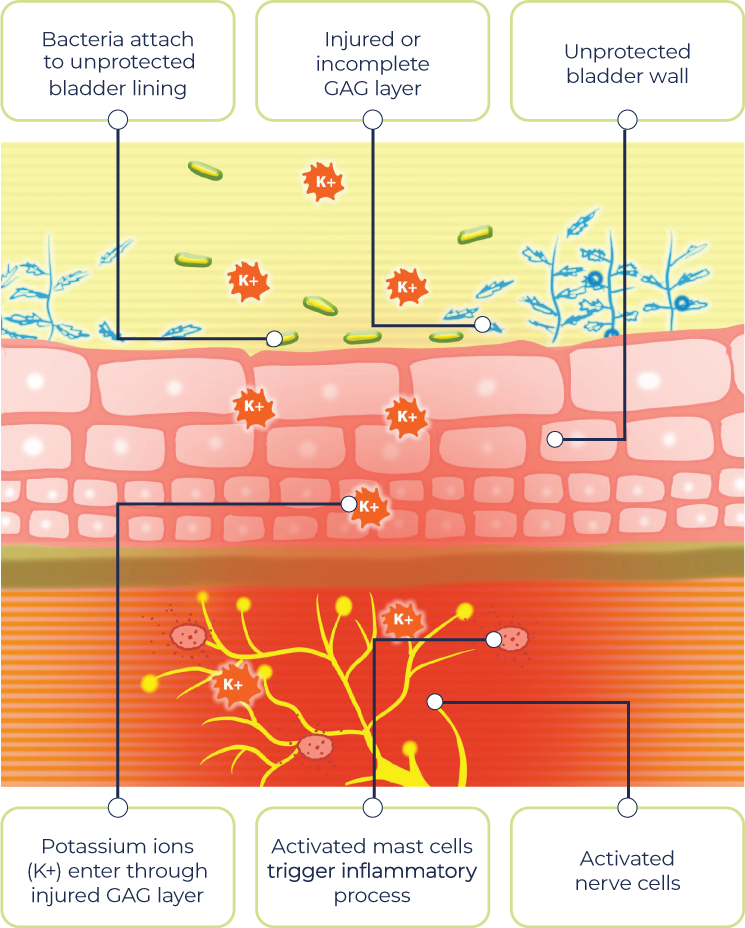

- Some people with BPS seem to have defects in the lining inside the bladder (medically called the glycosaminoglycan, or GAG, layer). When this layer becomes defective and leaky, it may allow irritating substances such as potassium and urea in the urine to enter the bladder wall and cause irritation and pain in the deeper layers

- There is evidence that a broken GAG layer struggles to heal itself properly after it has been damaged. This could be triggered by something like a urinary tract infection. Bacteria may attach to the unprotected bladder lining and invade the deeper layers. No one specific type of bacterial infection has been identified as the culprit yet

- There are signs of inflammation in the layers of the bladder wall. Several types of cells that are involved with the immune system, and which produce various compounds that cause inflammation, have been found in the bladder wall

- The most prominent immune cells found are mast cells, which produce a substance called histamine. Histamine makes sensations from the bladder feel more intense and can enhance pain and frequency, and cause inflammation and swelling

- This long-term inflammation and irritation in the bladder layers cause changes in the nerves that carry bladder sensations, which may mean that pain is felt from sensations that should not normally feel painful (such as bladder filling)

- We know people with bladder pain syndrome are also more likely to have other autoimmune diseases

- People describe a pain or pressure that feels like it’s coming from the bladder area; this is the most common feature of BPS

- However, pain could also feel like it’s coming from other parts of the pelvic area or spreading to other areas in the pelvis e.g. the urethra (the tube from your bladder through which the urine passes when you empty your bladder) or even the lower back. It may feel like it is spreading to other parts of the pelvic area

- The pain usually worsens as the bladder fills and eases after passing urine but soon returns

- Pain may be constant or it may come and go but may be there for several weeks or months

- “Frequency” is a term used to describe a constant or more frequent need to pass urine

- Under normal circumstances, an average person urinates no more than seven times a day and does not need to get up at night to urinate more than once

- People with BPS typically have to pass urine more often during the day and get up at night more than once to use the bathroom

- Some people with BPS may experience “urgency”, which is a sudden, compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to ignore.2 Meaning you have to go NOW! Others may not experience urgency as a severe symptom

- Other people with BPS may feel a constant urge to pass urine that never goes away, even after they have just been to the toilet

- Chronic ongoing bladder pain (constant or variable pain)

- A frequent need to urinate (more than seven times a day)

- Need to get up in the night to pass urine more than once

- Ongoing urge to pass urine that does not subside when bladder is empty

- Pain in other areas of the pelvic region

- Urinates no more than seven times a day

- Able to sleep through the night without the need to visit the bathroom more than once

- Urge to urinate subsides once bladder has been emptied

- No pain within the bladder when bladder fills or after emptying the bladder

Like all diseases, symptoms and how severe they are can vary from person to person. BPS is no different.

References

- European Association of Urology. Guidelines on chronic pelvic pain.

Available at: https://uroweb.org/guideline/chronic-pelvic-pain/#4. Accessed March 2020 - Hanno P, et al. Bladder pain syndrome international consultation on incontinence.

Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/65e2/1ca591824e3eb734e283d2cac21e409d9a13.pdf. Accessed January 2020

Classification

The way doctors classify BPS has changed over the years as more is known about the condition. Importantly, BPS is now recognised as more than just a bladder condition, and is now approached in a more holistic way as a chronic (long-lasting) pain syndrome.1,2

- Chronic pelvic pain, discomfort or pressure (lasting over 6 months) with the absence of infection or other identifiable causes

- Associated urinary symptoms (urgency, constant urge to pass urine which leads to more frequent visits to the toilet)

As some features of BPS are similar to those seen with other known conditions (including autoimmune diseases), the healthcare team will carry out a number of investigations to eliminate these other conditions before confirming a diagnosis of BPS.

Many doctors subdivide the condition into sub categories based on the presence or absence of tiny bleeds (glomerulations) and/or distinctive lesions or ulcers on the bladder wall (Hunner’s lesions). The second criteria they look at is the number of mast cells present in the bladder wall.

References

- Abrams P, et al. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21(2):167–78

- International Continence Society. IC/BPS.

Available at: https://www.ics.org/committees/standardisation/terminologydiscussions/icbps. Accessed March 2020

Diagnosis

Physical and neurological examination

- In women, the physical examination will likely focus on your abdomen, the organs in your pelvis, vagina and your rectum

- In men, a physical examination will look at your abdomen, prostate and rectum

A neurological examination might be performed to rule out any other problems that might be contributing to your bladder symptoms, including mental health and/or anxiety disorders.

Baseline pain assessment and bladder diary

Since the hallmark sign of BPS is pain, your healthcare team will conduct tests and ask you to complete a series of questionnaires to find out more about the pain you are experiencing and what may make it better or worse. This will also give your healthcare team a baseline so they can assess the effectiveness of any treatments or procedures.

The completion of a bladder diary will aid in the assessment of your bladder function by recording things like how much urine you pass and how often.

- Find pain location(s)

- Determine intensity

- Assess how the pain varies during the day and night and if it feels like it spreads somewhere else

- Identify factors that make pain or discomfort better/worse

- Determine voiding frequency – how often you empty your bladder and when in the day or night it is

- How much you drink compared to how much you pass urine. It may also show if certain drinks makes your symptoms worse

Voiding tests

“Voiding” is simply the medical term for urinating, emptying your bladder. A voiding test (or voiding cystourethrogram) is a medical examination that allows your doctor to look at how much urine your bladder can hold before you have the need to pass urine. They can also measure the pressure inside your bladder as it fills up and as you empty your bladder.

This test will be carried out in the hospital, where a doctor will use a thin flexible tube called a catheter to fill your bladder with a dye that can be detected on an X-ray.

Images are taken at various points as your bladder fills to determine how much urine your bladder can hold. The catheter is then removed and you will be asked to empty your bladder. Further X-ray images are taken to determine if there are abnormalities in the flow of urine and whether you are able to fully empty your bladder.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is a procedure that allows your doctor to look inside the bladder using a thin camera called a cystoscope.

- Tiny bleeds (glomerulations)

- Distinctive lesions/ulcers on the bladder wall (Hunner’s lesions)

- More mast cells than usual in the bladder lining

The thin camera is inserted through the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the bladder). Small samples of tissue may be taken for further testing (a ‘biopsy’).

- flexible cystoscopy – a thin (about the width of a pencil), bendy cystoscope. You stay awake while this is used to look at your bladder from the inside. Local anaesthetic is used to numb the urethra, so it is usually not painful, just a little uncomfortable. For further information, click here.

- rigid cystoscopy – a slightly wider cystoscope that doesn’t bend. You’re either put to sleep (i.e. under general anaesthetic) or the lower half of your body is numbed while this cystoscope is used. For further information click here.

Reference

- NHS UK. Cystoscopy overview.

Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cystoscopy/. Accessed March 2020

Physical and neurological examination

- In women, the physical examination will likely focus on your abdomen, the organs in your pelvis, vagina and your rectum

- In men, a physical examination will look at your abdomen, prostate and rectum

A neurological examination might be performed to rule out any other problems that might be contributing to your bladder symptoms, including mental health and/or anxiety disorders.

Baseline pain assessment and bladder diary

Since the hallmark sign of BPS is pain, your healthcare team will conduct tests and ask you to complete a series of questionnaires to find out more about the pain you are experiencing and what may make it better or worse. This will also give your healthcare team a baseline so they can assess the effectiveness of any treatments or procedures.

The completion of a bladder diary will aid in the assessment of your bladder function by recording things like how much urine you pass and how often.

- Find pain location(s)

- Determine intensity

- Assess how the pain varies during the day and night and if it feels like it spreads somewhere else

- Identify factors that make pain or discomfort better/worse

- Determine voiding frequency – how often you empty your bladder and when in the day or night it is

- How much you drink compared to how much you pass urine. It may also show if certain drinks makes your symptoms worse

Voiding tests

“Voiding” is simply the medical term for urinating, emptying your bladder. A voiding test (or voiding cystourethrogram) is a medical examination that allows your doctor to look at how much urine your bladder can hold before you have the need to pass urine. They can also measure the pressure inside your bladder as it fills up and as you empty your bladder.

This test will be carried out in the hospital, where a doctor will use a thin flexible tube called a catheter to fill your bladder with a dye that can be detected on an X-ray.

Images are taken at various points as your bladder fills to determine how much urine your bladder can hold. The catheter is then removed and you will be asked to empty your bladder. Further X-ray images are taken to determine if there are abnormalities in the flow of urine and whether you are able to fully empty your bladder.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is a procedure that allows your doctor to look inside the bladder using a thin camera called a cystoscope.

- Tiny bleeds (glomerulations)

- Distinctive lesions/ulcers on the bladder wall (Hunner’s lesions)

- More mast cells than usual in the bladder lining

The thin camera is inserted through the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the bladder). Small samples of tissue may be taken for further testing (a ‘biopsy’).

- flexible cystoscopy – a thin (about the width of a pencil), bendy cystoscope. You stay awake while this is used to look at your bladder from the inside. Local anaesthetic is used to numb the urethra, so it is usually not painful, just a little uncomfortable. For further information, click here.

- rigid cystoscopy – a slightly wider cystoscope that doesn’t bend. You’re either put to sleep (i.e. under general anaesthetic) or the lower half of your body is numbed while this cystoscope is used. For further information click here.

Reference

- NHS UK. Cystoscopy overview.

Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cystoscopy/. Accessed March 2020

Further tests

After performing some tests, your healthcare team may decide to refer you to a different hospital specialist, who may send you for further tests.

One of these tests might be a urodynamic evaluation. This involves filling the bladder with water through a thin tube called a catheter and involves measuring bladder pressures as the bladder fills and empties.1

This will not only give your doctor a good idea of what is going on inside your bladder, but also give an indication of how severe your BPS may be, so that your healthcare team can recommend the right treatment for you.

Reference

- Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. Having a urodynamics test.

Available at: https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/resources/patient-information/urology/procedures/having-a-urodynamics-test.pdf. Accessed March 2020

Back to top

Back to top